How May Cars Did Families Have in the 1950s

Tailfins gave a Space Historic period look to cars, and along with all-encompassing use of chrome became commonplace by the end of the decade.

1950s American automobile culture has had an enduring influence on the civilisation of the United States, as reflected in popular music, major trends from the 1950s and mainstream acceptance of the "hot rod" culture. The American manufacturing economy switched from producing war-related items to consumer goods at the terminate of Globe War Ii, and by the end of the 1950s, 1 in six working Americans were employed either directly or indirectly in the automotive industry. The Us became the world'south largest manufacturer of automobiles, and Henry Ford's goal of 30 years before—that any human with a expert job should be able to beget an auto—was achieved.[1] A new generation of service businesses focusing on customers with their automobiles came into being during the decade, including drive-through or bulldoze-in restaurants and more drive-in theaters (cinemas).

The decade began with 25 one thousand thousand registered automobiles on the road, most of which predated World War II and were in poor status; no automobiles or parts were produced during the state of war owing to rationing and restrictions. By 1950, most factories had made the transition to a consumer-based economic system, and more than 8 million cars were produced that year alone. Past 1958, in that location were more than than 67 1000000 cars registered in the United states, more than twice the number at the start of the decade.[2]

As part of the U.S. national defenses, to support military machine transport, the National Highway System was expanded with Interstate highways, beginning in 1955, across many parts of the United States. The wider, multi-lane highways allowed traffic to move at faster speeds, with few or no stoplights on the way. The broad-open up spaces along the highways became a basis for numerous billboards showing advertisements.

The dawning of the Space Age and Space Race were reflected in contemporary American automotive styling. Large tailfins,[three] flowing designs reminiscent of rockets, and radio antennas that imitated Sputnik ane were mutual, attributable to the efforts of design pioneers such as Harley Earl.[iv]

Interstate Highway System [edit]

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National Organisation of Interstate and Defense Highways (commonly called the Interstate Organization or simply the Interstate) is a network of freeways that forms a office of the National Highway System of the United States.

While serving as Supreme Commander of the Allied forces in Europe during World State of war II, Eisenhower had gained an appreciation of the German Autobahn network as an essential component of a national defense system, providing transport routes for military supplies and troop deployments.[5] Construction was authorized by the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, and the original portion was completed 35 years later. The system has contributed in shaping the Usa into a globe economic superpower and a highly industrialized nation.[6]

The Interstate grew quickly, forth with the automobile industry, allowing a new-found mobility that permeated ways of American life and culture. The automobile and the Interstate became the American symbol of individuality and liberty,[7] and, for the outset time, automobile buyers accustomed that the automobile they drove indicated their social standing and level of affluence. It became a statement of their personality and an extension of their self-concepts.[8]

Suburbanization [edit]

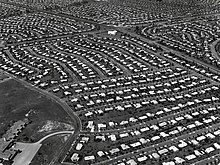

The Usa' investment in infrastructures such as highways and bridges coincided with the increasing availability of cars more suited to the college speeds that ameliorate roads made possible, assuasive people to alive beyond the confines of major cities, and instead commute to and from piece of work.[9]

After World War II, country developers began to buy land just outside the city limits of larger cities to build mass quantities of inexpensive tract houses.[10] I of the get-go examples of planned suburbanization is Levittown, Pennsylvania, which was developed by William Levitt beginning in 1951 as a suburb of Philadelphia.[two] The promise of their own unmarried-family home on their ain land,[11] together with a complimentary higher instruction and low-interest loans given to returning soldiers to purchase homes nether the 1000.I. Bill, drove need for new homes to an unprecedented level. Additionally, 4 million babies were born every year during the 1950s. Past the end of the babe nail era in 1964, virtually 77 meg "baby boomers" had been born,[10] fueling the need for more suburban housing, and automobiles to commute them to and from the urban center centers for work and shopping.

Past the finish of the 1950s, ane-third of Americans lived in the suburbs. Xi of the United States'due south twelve largest cities recorded a declining population during the decade, with a consistent loss in taxation revenues and city culture. Only Los Angeles, a center for the car civilisation, gained population.[12] Economist Richard Porter commented that "The automobile made suburbia possible, and the suburbs made the automobile essential."[13]

Decline of the inner metropolis [edit]

More people joined the heart form in the 1950s, with more coin to spend, and the availability of consumer goods expanded along with the economy, including the automobile.[x] Americans were spending more time in their automobiles and viewing them equally an extension of their identity, which helped to fuel a nail in automobile sales.[seven] Virtually businesses directly or indirectly related to the auto manufacture saw tremendous growth during the decade. New designs and innovations appealed to a generation tuned into fashion and glamour,[8] and the new-establish freedom and way of life in the suburbs had several unforeseen consequences for the inner cities. The 1950s saw the starting time of white flight and urban sprawl, driven by increasing automobile ownership. Many local and national transportation laws encouraged suburbanization, which in fourth dimension ended upwards damaging the cities economically.[14]

Auto-related magazines became common in the 1950s

As more centre-course and flush people fled the city to the relative tranquillity and open spaces of the suburbs, the urban centers deteriorated and lost population.[15] At the same time that cities were experiencing a lower tax base due to the flight of college income earners, pressures from The New Bargain forced them to offer pensions and other benefits, increasing the average price of benefits per employee past 1,629 percent. This was in add-on to hiring an average of 20 per centum more employees to serve the ever shrinking cities.[xv] More than Americans were driving cars and fewer were using public transportation, and it was not practical to extend to the suburbs.[13] At the same time, the number of surface roads exploded to serve the e'er-increasing numbers of individually owned cars, further burdening urban center and land resources. During this time, the perception of using public transportation turned more negative. In what is arguably the near extreme instance, Detroit, the fifth largest city in the United States in 1950 with 1,849,568 residents,[16] had shrunk to 706,585 by 2010,[17] a reduction of 62 percent.

In some instances, the automotive manufacture and others were directly responsible for the turn down of public transportation.[xiii] The Groovy American streetcar scandal saw GM, Firestone Tire, Standard Oil of California, Phillips Petroleum, Mack Trucks and other companies purchase a number of streetcars and electric trains in the 1930s and 1940s, such that xc percent of city trolleys had been dismantled by 1950. It was argued that this was a deliberate devastation of streetcars as role of a larger strategy to push the United States into automobile dependency.[18] In The states v. National Metropolis Lines, Inc., many were establish guilty of antitrust violations.[19] The story has been explored several times in print, film and other media, for example in Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Taken for a Ride and The Finish of Suburbia.

Women's rights [edit]

The automobile unions played a leading role in advancing the cause of women's rights. In 1955, the United Car Workers Union (UAW) organized the UAW Women's Department to strengthen women's office in the union and encourage participation in the union's elected bodies. In a movement that was met with some hostility by Teamsters leaders, the U.South. Division of Transport Personnel had in 1943 instructed Teamsters Union officials that women should exist allowed full employment as truck drivers. That proved to exist merely a temporary wartime measure,[21] but a modify of heart among Teamsters leadership past the mid-1950s led to the Equal Pay Human activity of 1963. Women in the car manufacture were considered leaders in the movement for women's rights.[22]

Motorsports [edit]

Hot rodding [edit]

The increasing popularity of hot rodding cars (modifying them to increase performance) is reflected in role past the creation of special-involvement magazines catering to this culture. Hot Rod is the oldest such magazine, with first editor Wally Parks[23], and founded by Robert East. Petersen in 1948, with original publication by his Petersen Publishing Company.[23] Hot Rod has licensed amalgamation with Universal Technical Institute.[24]

The relative affluence and inexpensive nature of the Ford Model T and other cars from the 1920s to 1940s helped fuel the hot rod culture that developed, which was focused on getting the almost linear speed out of these older automobiles. The origin of the term "hot rod" is unclear, just the culture blossomed in the post-war civilization of the 1950s.[25]

Hot Rod magazine's November 1950 comprehend announced the showtime hot rod to exceed 200 mph. The manus-crafted car used an Edelbrock-built Mercury flathead V8 and fix the tape at the Bonneville Common salt Flats.[26] This 30,000-acre (47 sq mi) region[27] has been called the "Holy Grail of American Hot Rodding", and is oftentimes used for country speed racing, a tradition that grew rapidly in the 1950s and continues today.[28]

Hot rodding was about more than raw power. Kustom Kulture started in the 1950s,[29] when artists such as Von Dutch transformed machine pin striping from a seldom-used accent that followed the lines of the automobile into a freestyle art form. Von Dutch was every bit famous for his "flying eyeball"[29] every bit he was for his intricate spider-web designs.[thirty] As the decade began, hand-drawn pin striping was almost unheard of, but by 1958 it had get a pop method of customizing the looks of the hot rod.[30] As the decade progressed, hot rodding became a pop hobby for a growing number of teenagers as the sport literally came to Main Street.[31]

Drag racing [edit]

Drag racing has existed since the beginning cars, but it was not until the 1950s that it started to become mainstream, starting time with Santa Ana Drags, the showtime drag strip in the United States.[32] The strip was founded by C. J. "Pappy" Hart, Creighton Hunter and Frank Stillwell at the Orangish County Airport auxiliary rails in southern California, and was operational from 1950 until June 21, 1959.[33]

Hot Rod editor Wally Parks created the National Hot Rod Association in 1951, and information technology is even so the largest governing body in the popular sport.[32] Equally of October 2012[update], there are at least 139 professional drag strips operational in the United States.[34] One of the most powerful racing fuels ever developed is nitromethane, which dramatically debuted as a racing fuel in 1950, and continues equally the primary component used in Pinnacle Fuel elevate racing today.[35] While nitromethane had been around for years and was used as an industrial solvent, information technology was commencement used equally a racing fuel in 1954. [36] [37]

NASCAR [edit]

NASCAR winner "The Fabled Hudson Hornet"

The National Association for Stock Machine Automobile Racing (NASCAR) is the second near popular spectator sports in the The states backside the National Football League (NFL).[38] Information technology was incorporated on February 21, 1948, by Bill French republic, Sr. and built its roots in the 1950s.[39] Ii years later in 1950 the first asphalt "superspeedway", Darlington Speedway, was opened in South Carolina, and the sport saw dramatic growth during the 1950s.[39] Because of the tremendous success of Darlington, construction began of a ii+ i⁄ii -mile (4.0 km), loftier-banked superspeedway near Daytona Embankment, which is still in use.[39]

The Loving cup Series was started in 1949, with Jim Roper winning the first series.[39] By 2008, the most prestigious race in the series, the Daytona 500 had attracted more than 17 meg telly viewers.[40] Dynasties were born in the 1950s with racers like Lee Trivial (male parent of Richard Petty, grandfather of Kyle Fiddling) and Buck Baker (father of Buddy Baker).

NASCAR, and stock car racing in general, has its roots in bootlegging during Prohibition.[41] Junior Johnson was one of many bootleggers who took role in the sport during the 1950s, equally well known for his arrest in 1955 for operating his father'southward moonshine still as he is for his racing success.[42] He concluded upward spending a year in an Ohio prison,[43] but soon returned to the sport before retiring every bit a driver in 1966.[41]

New business models [edit]

Faster food [edit]

Drive-ins take orders over an intercom system, with a carhop accepting payment and delivering the social club on a tray that attaches to the automobile window.

Every bit more Americans began driving cars, entirely new categories of businesses came into existence to allow them to savor their products and services without having to exit their cars. This includes the drive-in eatery, and subsequently the bulldoze-through window. Fifty-fifty into the 2010s, the Sonic Drive-In eating house concatenation has provided primarily drive-in service by carhop in iii,561 restaurants within 43 U.S. states, serving approximately three million customers per day.[44] [45] Known for its use of carhops on roller skates, the company annually hosts a contest to make up one's mind the top skating carhop in its organisation.[46]

A number of other successful "drive up" businesses have their roots in the 1950s, including McDonald's (expanded c. 1955), which had no dine-in facilities, requiring customers to park and walk up to the window, taking their gild "to go". Automation and the lack of dining facilities allowed McDonald's to sell burgers for 15 cents each, instead of the typical 35 cents, and people were buying them by the bagful. Past 1948, they had fired their carhops, installed larger grills, reduced their bill of fare and radically changed the industry by introducing assembly-line methods of food product, similar to the motorcar industry, dubbing it the "Speedee Service Arrangement".[47] They redesigned their sign specifically to go far easier to see from the road, creating the now familiar yellow double-arch structure.[48] Man of affairs Ray Kroc joined McDonald's equally a franchise amanuensis in 1955. He subsequently purchased the chain from the McDonald brothers and oversaw its worldwide growth.[49]

Other chains were created to serve the increasingly mobile patron. Carl Karcher opened his first Carl'south Jr. in 1956, and rapidly expanded, locating his restaurants near California's new throughway off-ramps.[fifty] These restaurant models initially relied on the new and ubiquitous ownership of automobiles, and the willingness of patrons to dine in their automobiles. Every bit of 2013[update], drive-through service account for 65 percent of their profits.[51]

Drive-in movies [edit]

The drive-in theater is a form of cinema structure consisting of a large outdoor movie screen, a projection booth, a concession stand and a big parking area for automobiles, where patrons view the flick from the condolement of their cars and listen via an electric speaker placed at each parking spot.

Although drive-in movies get-go appeared in 1933,[52] it was not until well after the postal service-war era that they became pop, enjoying their greatest success in the 1950s, reaching a pinnacle of more than 4,000 theaters in the The states alone.[53] [54] Drive-in theaters have been romanticized in popular culture with the motion-picture show American Graffiti and Grease and the goggle box serial Happy Days. They developed a reputation for showing B movies, typically monster or horror films, and every bit "passion pits", a place for teenagers to make out.[54] While bulldoze-in theaters are rarer today with only 366 remaining[53] and no longer unique to America, they are still associated as office of the 1950s' American car civilisation.[55] By the beginning of 2020, the number of fully operational drive-ins has dropped to xx.[56] Drive-in movies take seen somewhat of a resurgence in popularity in the 21st century, due in part to baby boomer nostalgia, every bit well every bit some increased interest during the COVID-nineteen pandemic in the Us, which forced conventional movie theaters to close.. [54] [56]

Robert Schuller started the nation's beginning drive-in church building in 1955 in Garden Grove, California. After his regular 9:30 am service in the chapel iv miles (six km) away, he would travel to the drive-in for a 2nd Sunday service.[57] Worshipers listened to his sermon from the comfort of their cars, using the movie house'south speaker boxes.[58]

Malls [edit]

The first modern shopping malls were congenital in the 1950s,[59] such every bit Bergen Mall, which was the get-go to employ the term "mall" to describe the business organization model. Other early malls moved retailing away from the dense, commercial downtowns into the largely residential suburbs. Northgate in Seattle is credited every bit being the first modern mall blueprint, with two rows of businesses facing each other and a walkway separating them. It opened in 1950. Shopper's World in Framingham, Massachusetts, was the kickoff 2-story mall, and opened in 1951.[59] The design was modified again in 1954 when Northland Center in Detroit, Michigan, used a centralized design with an anchor shop in the middle of the mall, ringed by other stores. This was the start mall to accept the parking lot completely surrounding the shopping center, and to provide central heat and air-conditioning.[59]

In 1956, Southdale Eye opened in Edina, Minnesota. It was the first to combine these modern elements; enclosed with a ii-story pattern, central heat and ac plus a comfortable common area. It featured two large section stores as anchors. Most industry professionals consider Southdale Center to be the first modernistic regional mall.[59]

This formula (enclosed space with stores attached, away from downtown and attainable only by motorcar) became a popular way to build retail across the earth. Victor Gruen, one of the pioneers in mall design,[threescore] came to abhor this result of his new pattern. He decried the creation of enormous "state wasting seas of parking" and the spread of suburban sprawl.[61]

Aftermarket auto parts [edit]

The 1950s spring started an manufacture of aftermarket add-ons for cars that continues today. The oldest aftermarket wheel company, American Racing, started in 1956 and still builds "mag wheels" (alloy wheels) for near every car made.[62] Holley introduced the starting time modular iv-barrel carburetor, which Ford offered in the 1957 Ford Thunderbird,[63] and versions are still used by performance enthusiasts. Edelbrock started during the Great Depression and expanded after the war. They provided a multifariousness of high performance parts for the new hot rodders, which was pop equipment for setting speed records at Bonneville Table salt Flats.[64] Owners were no longer restricted to the original equipment provided by manufacturers, helping not only create the hot rod civilization[65] but also the foundation for cosmetic modifications. The creation and rapid expansion of the aftermarket fabricated it possible for enthusiasts to personalize their automobiles.[66]

Distribution [edit]

Crosley autos were sold in a number of appliance stores in the early 1950s.

Nigh new cars were sold through car dealerships in the 1950s, but Crosley automobiles were still on auction at any number of appliance or department stores,[67] [68] and Allstate (a rebadged Henry J) could exist ordered at any Sears and Roebuck in 1952 and 1953.[69] By mid-decade, these outlets had vanished and the automobile dealer became the sole source of new automobiles.

Starting in the mid-1950s, new car introductions in the fall once more became an predictable effect, every bit all dealers would reveal the models for the upcoming year each October. In this era before the popularization of computerization, the primary source of information on new models was the dealer.[lxx] The idea was originally suggested in the 1930s by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Great Depression, as a way of stimulating the economy by creating need. The idea was reintroduced by President Dwight Eisenhower for the same reasons, and this method of introducing adjacent twelvemonth's models in the preceding autumn lasted well into the 1990s.[70]

During the decade, many smaller manufacturers could not compete with the Big Iii and either went out of business[71] or merged. In 1954, American Motors was formed when Hudson merged with Nash-Kelvinator Corporation in a deal worth almost $200 million, the largest corporate merger in United States history at that time.[72]

Musculus cars [edit]

The muscle-car era is deeply rooted in the 1950s,[73] although there is some fence equally to the exact beginning. The 1949 Oldsmobile Rocket 88, created in response to public interest in speed and power, is often cited as the offset muscle car. It featured America's commencement high-pinch overhead valve V8 in the smaller, lighter Oldsmobile 76/Chevy body for six-cylinder engines (as opposed to bigger Olds 98 luxury trunk).[74] Old Cars Weekly claims it started with the introduction of the original Chrysler "Firepower" hemi V8 engine in 1951,[75] while others such every bit Hot Rod magazine consider the first overhead valve engine past Chevrolet, the 265 cid V8, every bit the "heir apparent to Ford flathead's position as the staple of racing", in 1955.[76] The "pocket-sized block Chevy" itself developed its own subculture that exists today.[77] Other contenders include the 1949 Oldsmobile V8 engine, the start in a long line of such powerful V8 engines,[78] [79] as well every bit the Cadillac V8 of the same twelvemonth.[eighty]

Regardless how it is credited, the horsepower race centered around the V8 engine[73] [81] and the muscle-car era lasted until new smog regulations forced dramatic changes in OEM engine design in the early on 1970s. This in turn opened upwards new opportunities for aftermarket manufacturers like Edelbrock.[76] Each twelvemonth brought larger engines and/or increases in horsepower,[82] providing a catalyst for customers to upgrade to newer models. Motorcar executives as well deliberately updated the torso designs yearly, in the proper noun of "planned obsolescence"[83] [84] and added newly developed or improved features such as automatic transmissions, ability steering, power brakes and prowl control, in an attempt to brand the previous models seem outdated and facilitate the long drive from the suburbs.[82] Record sales made the decade arguably the "golden era" of machine manufacturing.[85]

Harley Earl and Beak France Sr. popularized the saying "Race on Sunday, sell on Mon",[86] a mantra even so heard today in motorsports, particularly within NASCAR. During the muscle-car era, manufacturers not only sponsored the drivers, but designed stock cars specifically to compete in the fast-growing and highly popular sport.[73]

Songs celebrating the automobile [edit]

As the automobile became more and more than an extension of the private, it was natural for this to be reflected in popular culture. America's love matter with the auto was most evident in the music of the era.

- "Rocket 88" was starting time recorded in 1951 and originally credited to Jackie Brenston and his Delta Cats, although it was later discovered to be the piece of work of Ike Turner's Kings of Rhythm. Information technology is often credited as the starting time rock and ringlet song ever produced[87] and has been covered by other artists.

- "Hot Rod Lincoln" was first recorded in 1955 by Charlie Ryan,[88] [89] and has since been recorded by Roger Miller and others.[90] The 1960 Johnny Bond version charted at number 26 on Billboard Hot 100. Comedian Jim Varney produced a version with Ricky Skaggs for the motility picture The Beverly Hillbillies.[91] The song is still a popular live song for artists such as Asleep at the Wheel[92] and Inferior Dark-brown.[93]

- "Maybellene", released past Chuck Berry in 1955, is an uptempo rocker describing a hot rod race between a jilted lover and his unfaithful girlfriend. It was a #five hitting and was described past Rolling Stone as the starting bespeak of rock and roll guitar.[94]

- "Wake Upwards Little Susie" recorded by The Everly Brothers, reached number one on the Billboard Popular chart, despite having been banned from Boston radio stations for lyrics virtually elaborating "our reputation is shot" considering the narrator and his date slept through a drive-through movie date and missed their curfew by six hours.[95]

- "Teen Angel" was released in 1959 and initially met with resistance by radio stations because of its nighttime message about a young girl who dies in an machine/railroad train blow.

Other songs recorded during the decade as well reflect the automobile's place in American civilization, such as "Brand New Cadillac", Sonny Burgess's "Thunderbird" and Bo Diddley's "Cadillac". A 1955 Oldsmobile was celebrated in the nostalgic "Ol' '55" by Tom Waits (1973).

Meet besides [edit]

- American machine industry in the 1950s

- Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1952

- Listing of motorcar crash songs

- List of defunct automobile manufacturers of the U.s.

- History of the automobile

- Timeline of motor vehicle brands

- Cruising

- Elvis' Pink Cadillac

- Full general Motors Motorama

- Raggare

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Weiss (2003), p. 34.

- ^ a b Reid, Keight (June 2004). "Happy days – For petroleum marketers, the 1950s lived up to the nostalgia". National Petroleum News: 24–25.

- ^ Gunnell (2004), p. xv.

- ^ "Tail Fins Rising". Machine Designer Pioneer Harley Earl – America's First Engineer of Desire. Car of the Century.com. Archived from the original on Nov 19, 2012. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ Petroski, Henry (2006). "On the Road". American Scientist. 94 (5): 396–99. doi:ten.1511/2006.61.396. ISSN 0003-0996.

- ^ Weingroff, Richard F. (September–October 2000). "The Genie in the Bottle: The Interstate System and Urban Issues, 1939–1957". Public Roads. Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. 64 (2). ISSN 0033-3735. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- ^ a b "The Geography of Transport Systems – The Interstate Highway Arrangement". Hofstra University. Retrieved October xiv, 2012.

- ^ a b "America on the Move – Making the Sale". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ Vebell, Ed (February 1958). "Popular Mechanics". Popular Mechanics Mag. Hearst Magazines: 144. ISSN 0032-4558. Retrieved December ii, 2012.

- ^ a b c "The 1950s". The History Aqueduct. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ Hosack, Walter Martin (2001). Land Development Calculations (8 ed.). McGraw Colina Professional. p. 133. ISBN978-0-07-136255-nine. "single-family discrete housing" = "suburb houses"

- ^ "Society in The 1950s". Shmoop. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ a b c Dauvergne (2008), p. 38.

- ^ "America on the Move – The Sprawling Metropolis". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved October xv, 2012.

- ^ a b Greenberg, Brian; Watts, Linda S.; Greenwald, Richard A.; Reavley, Gordon; George, Alice L.; Beekman, Scott; Bucki, Cecelia; Ciabattari, Mark; Stoner, John C.; Paino, Troy D.; Mercier, Laurie; Chase, Andrew; Hollaran, Peter C.; Cohen, Nancy (October 23, 2008). Social History of the United States. ABC-CLIO. p. 5. ISBN978-one-59884-128-ii . Retrieved Dec 1, 2012.

- ^ "US Census – Largest Cities in 1950". United states Dept. of Census. June 15, 1998. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- ^ "Table 1. Almanac Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places Over 50,000, Ranked by July 1, 2011 Population: April one, 2010, to July one, 2011". 2011 Population Estimates. The states Census Bureau, Population Division. June 2012. Archived from the original (CSV) on August 21, 2012. Retrieved August i, 2012.

- ^ Snell, Bradford (February 26, 1974). "Argument of Bradford C. Snell Before the United States Senate Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly" (PDF). Hearings on the Ground Transportation Industries in Connection with S1167. S.C.R.T.D. Library. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ Lindley, Walter (January iii, 1951). "U.s.a. five. National City Lines, Inc., et al". United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. Archived from the original on June viii, 2008. Retrieved April five, 2009.

- ^ Vosko, Leah F.; Witwer, David (September 2001). "'Non A Human'S Spousal relationship': Women Teamsters in the Us during the 1940s and 1950s". Periodical of Women'southward History. 13 (3): 169–192. doi:10.1353/jowh.2001.0078. S2CID 144152385.

- ^ Walsh, Margaret. "Gender and the Automobile in the The states". Gender on the Line.

- ^ a b Thacker, Tony. "NHRA Founder Wally Parks Passes". hotrod.com. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- ^ Hot Rod Magazine. "UTI Automotive Technology Program – Hot Rod U – Prepare To Brand A Living Doing What You Dear?". Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- ^ Genat, Cox & Parks (2003), p. 41.

- ^ Taylor, Thom (January 2013). "The Beginning 200-MPH Hot Rod". Hot Rod: 36–43.

- ^ "Bonneville Salt Flats History". U.S. Section of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- ^ Abbey, Bob (June 19, 2011). "Management of the Bonneville Table salt Flats in Western Utah" (PDF). U.South. Section of the Interior, Agency of Land Management. Archived from the original (PDF) on March four, 2016. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- ^ a b DeWitt, Jack (September–October 2010). "Cars and Culture: The Cars of "American Graffiti."". American Poetry Review. 39 (5): 47–fifty. ISSN 0360-3709.

- ^ a b "Von Dutch's Kenford work truck". Barracuda #7. Barracuda Magazine.

- ^ Freiburger, David (June 2012). "Real Rods of the '50s – The 18-carat Article". Hot Rod Magazine. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ a b "NHRA history: Drag racing's fast kickoff". National Hot Rod Clan. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved Oct xiv, 2012.

- ^ Prieto, Don (1999). "Santa Ana Drags ... The End of an Era". wediditforlove.com. Retrieved Oct 14, 2012.

- ^ "Dragstrips Drag Racing Tracks Directory". Drag Times. Retrieved Oct 15, 2012.

- ^ "Nitromethane: Meridian-Fuel Drag Racing's Soup of Choice". Drag Times. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ ""Nitromethane Was Discovered Every bit A Racing Fuel Way Back In 1954"". Garage Tech with Randy Rundle. September 13, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ Ron Lewis (March 27, 2013). ""What is Nitromethane, Anyway?"". Motor Tendency. Retrieved Oct 30, 2021.

- ^ Badhausen, Kurt (June 17, 2012). "All Of Nascar Gets Boost With A Dale Earnhardt Win". Forbes . Retrieved December two, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "History of NASCAR – Pecker France Sr.'s vision at present staple of sports mural". NASCAR.com. March eight, 2010. Retrieved December ii, 2012.

- ^ "2009 NASCAR Sprint Cup TV Ratings". Archived from the original on September 9, 2011. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ a b Houston, Rick (November ane, 2012). "The Moonshine mystique – NASCAR'due south earliest days forever connected to bootlegging". NASCAR. Retrieved December two, 2012.

- ^ Wolfe, Tom (May 23, 2010). "The Last American Hero Is Inferior Johnson. Yes!". Esquire. Archived from the original on January 10, 2012. Retrieved December ii, 2012.

- ^ Menzer (2001), p. 59.

- ^ "Business". Form 10-K Annual Written report. Sonic Drive-In. October 28, 2011. Archived from the original on April 24, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ^ Phelps, Jonathan (September 9, 2009). "Sonic Bulwark Broken – 1950s-Style Bulldoze-In Food Chain, Long Awaited by Its Fans, Arrives in Mass. with a Nail, and Traffic Jams Follow". The Boston World . Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- ^ Polish, Conor (September 13, 2011). "Sonic carhops skating for the large prize". Las Vegas Sun . Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ Schlosser (2001), pp. 19–20.

- ^ Schlosser (2001), p. xx.

- ^ "McDonald's History". Aboutmcdonalds.com. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- ^ Schlosser (2001), pp. 21–22.

- ^ Vanderbilt, Tom (December 11, 2009). "Has the American romance with the drive-through gone sour?". Slate . Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ Sanders & Sanders (2003), p. 162.

- ^ a b Hing, Regina (June 2, 2012). "Reborn: American Drive-In Motion picture Theaters". CNBC. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved Dec iii, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Drive-In Theater". TV Tropes. Archived from the original on Dec 8, 2012. Retrieved Dec 3, 2012.

- ^ Sanders & Sanders (2003), p. iv.

- ^ a b Drew Weisholtz (April 22, 2020). "Why bulldoze-in motion picture theaters are the slice of nostalgia we need right now". NBC News - Today Prove. Retrieved March 28, 2021.

- ^ Penner, James (1992). Goliath: The Life of Robert Schuller . p. 119.

- ^ Schlosser (2001), p. 19.

- ^ a b c d Kavanagh, Malachy (June 2000). "A Brief History Of Shopping Centers". International Council of Shopping Centers. Archived from the original on December 4, 2012. Retrieved December iv, 2012.

- ^ Bathroom Reader's Plant (November 2010). "The Mall: A History". Uncle John's Heavy Duty Bathroom Reader. Baker & Taylor Pub. pp. 99–101. ISBN978-1-60710-183-three.

- ^ Bathroom Reader's Establish (November 2010). "A History of the Shopping Mall, Part 3". Uncle John's Heavy Duty Bath Reader. Bath Reader'south Printing. p. 401. ISBN978-ane-60710-183-3.

- ^ "American Racing takes on the Hot Rod Power Tour". American Racing. May 14, 2012. Archived from the original on January xvi, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ "Holley History". Holley. Retrieved October xiv, 2012.

- ^ "The History Of Edelbrock Performance". Edelbrock. Archived from the original on October 21, 2007. Retrieved December iii, 2012.

- ^ Lucsko (2008), p. 105.

- ^ Dregni & Williams (2010), p. 35.

- ^ Cincinnati Magazine. Emmis Communications. February 2007. p. 185. ISSN 0746-8210. Retrieved December iv, 2012.

- ^ Genat & Newhardt (2007), p. 164.

- ^ Genat & Newhardt (2007), p. 165.

- ^ a b Romeo, Frank (Baronial 25, 2012). "Unveiling a car used to exist a party". Wheels. Toronto Star. p. W10. ISSN 0319-0781.

- ^ D'Argis, Larry (September 24, 2010). "Gonna buy me a Mercury". Winnipeg Complimentary Press. p. F4. Viewed Dec vi, 2012.

- ^ Quella, Chad. "The Spirit Is Still Alive: American Motors Corporation 1954–1987". AllPar. Retrieved October 20, 2012.

- ^ a b c Genat, Robert (Nov 15, 2004). The American Car Dealership. MotorBooks International. pp. 12–25. ISBN978-0-7603-1934-v . Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ Auto editors ofConsumer Guide (16 January 2007). "The Birth of Muscle Cars". musclecars.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 18 January 2016. Dulcich, Steve (August 2007). "Rocket Man". Popular Hot Rodding. Retrieved eighteen January 2016.

- ^ Staff of Old Cars Weekly (September sixteen, 2010). Nothin' But Musculus. Krause Publications. p. 84. ISBN978-1-4402-1755-v . Retrieved Dec 5, 2012.

- ^ a b Taylor, Thom (January 2013). "Edelbrock: 75 Years". Hot Rod: 72–77.

- ^ Mueller, Mike (May 15, 2005). Chevy Pocket-size-Cake 5-eight: fifty Years Of High Operation. MotorBooks International. p. 258. ISBN978-0-7603-2103-four . Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ Mueller, Mike (2004). The Essential Muscle Car. MotorBooks International. p. 12. ISBN978-0-7603-1966-6 . Retrieved Dec 4, 2012.

- ^ Ambrogio, Anthony; Luckerman, Sharon (2006). Cruisin' the Original: Woodward Avenue. Arcadia. p. 42. ISBN978-0-7385-4045-0 . Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ Huntington, Roger (December 1984). "American Cars – The First Century". Popular Mechanics: 78–79, 118–20.

- ^ "The Horsepower Race: It Doesn't Endanger Safety". Time. October 24, 1955. Archived from the original on December xv, 2008. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ a b Genat & Newhardt (2007), p. 7.

- ^ Beder, Sharon (Nov 1998). "Is planned obsolescence socially responsible?". Engineers Australia. Academy of Wollongong (originally Engineers Australia). p. 52. Retrieved December half-dozen, 2012.

- ^ Gartman, David. "1950s Scholarship on Design: Snobby Criticism and Populist Praise". A History of Scholarship on American Auto Blueprint. University of Michigan. Retrieved Dec 6, 2012.

- ^ "What Drives The Dream". Car Designer Pioneer Harley Earl — America'due south First Engineer of Desire. Motorcar of the Century.com. Archived from the original on Dec 24, 2012. Retrieved Dec 6, 2012.

- ^ "RACE ON SUNDAY, SELL ON MONDAY". Car of the Century.com. Archived from the original on Dec 26, 2010. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ Dahl, Neb. "Jackie Brenston Biography". AllMusic . Retrieved December v, 2012.

- ^ "Hot Rod Lincoln". Hot-Rod-Lincoln.com. Archived from the original on Nov 16, 2012. Retrieved December iii, 2012.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. "Crazy 'Bout an Automobile". AllMusic . Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "A Man Like Me: The Early Years of Roger Miller". AllMusic . Retrieved Dec 3, 2012.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "Original Soundtrack — The Beverly Hillbillies". AllMusic . Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- ^ "Asleep at the Wheel — Hot Rod Lincoln". Allmusic . Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- ^ "Bellys Up". marqueehq.com. Retrieved Dec 3, 2012.

- ^ "Maybellene". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on Dec 28, 2006. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ^ "Wake Upwardly Little Susie: The Everly Brothers : Rolling Rock". Rolling Rock. Archived from the original on May 12, 2006.

Bibliography [edit]

- Dauvergne, Peter (2008). The Shadows of Consumption: Consequences for the Global Environment. MIT Press. ISBN978-0-262-04246-8.

- Dregni, Michael; Williams, Robert (2010). The All-American Hot Rod: The Cars, the Legends, the Passion. MotorBooks International. ISBN978-0-7603-3828-five.

- Genat, Robert; Cox, Don; Parks, Wally (2003). The Birth of Hot Rodding: The Story of the Dry Lakes Era. MotorBooks International. ISBN978-0-7603-1303-9.

- Gunnell, John (2004). Standard Guide To 1950s American Cars . Krause Publications. ISBN978-0-87349-868-five.

- Lucsko, David North. (2008). The Concern of Speed: The Hot Rod Industry in America, 1915–1990. JHU Press. ISBN978-0-8018-8990-5.

- Menzer, Joe (2001). The Wildest Ride: A History of NASCAR. Simon & Schuster. ISBN978-0-7432-0507-8.

- Sanders, Don; Sanders, Susan (Baronial 1, 2003). The American Drive-In Movie Theater. MBI Publishing Company. ISBN978-0-7603-1707-v.

- Schlosser, Eric (2001). Fast Nutrient Nation: The Nighttime Side of the All-American Meal. Beginning Mariner Books. ISBN978-0-547-75033-0.

- Weiss, H. Eugene (2003). Chrysler, Ford, Durant, and Sloan: Founding Giants of the American Automotive Industry. McFarland. ISBN978-0-7864-1611-0.

- Genat, Robert; Newhardt, David (2007). American Cars of the 1950s. Motorbooks, MBI Publishing Company, LLC. ISBN978-0-7603-3230-six.

External links [edit]

- Hot Rod mag covers from the 1950s

- The one-time automobile manual project

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1950s_American_automobile_culture

Post a Comment for "How May Cars Did Families Have in the 1950s"